Bobby Earl Hurst lived the majority of his life in a part of the United States where his name carried incredible vocation versatility. A Florida resident, Bobby Earl Hurst could have been an SEC football coach in a Dan Jenkins novel. In a slight stretch, Bobby Earl’s voice and face had similarity to Bobby Cleckler Bowden, the legendary coach at Florida State, an ACC school and the favorite team of Bobby Earl’s daughter, Susan, who attended FSU.

How about Bobby Earl Hurst, elected official? Thankfully, no, that wasn’t his calling, either, which is not disrespectful but recognition that this country’s present political climate is already in enough disarray. Bobby did have a resemblance, my daughter, Joelle, first observed to me, to Lyndon B. Johnson, who perhaps Bobby might have lined up with politically at one point, both of them born in Texas. LBJ famously went nose-to-nose with both allies and adversaries alike and Bobby would have been the latter based on how his political opinions played out.

What about just Bobby Hurst, salesman? Now we’ve come to the man’s calling. Bobby Hurst became one of central Florida’s most successful boat dealers with his “Bob’s Boats and Motors” store on East Colonial Drive in Orlando. Bobby had married my wife, Mary’s, Aunt Lorraine Blondeel. To study the circular path Lorraine and Bobby took to meeting each other is to see the evidence of how Lorraine was Bobby’s one and only true love of his life. Lorraine was born on the family farm in Mineral, Illinois, on April 24, 1930. She went to Knox College in Galesburg and was living in Waukegan, Illinois, north of Chicago along Lake Michigan. Bobby was in the same vicinity in Great Lakes, Illinois, just south of Waukegan, stationed at Naval Station Great Lakes. He had been born in 1929 in Dalhart, a town located in the “chimney” portion of Texas. His family moved to the Oroville, California, area; Bob was the oldest of six siblings. After high school he went into the U.S. Navy, served four years, met Lorraine while at the Naval Base, and the two married in 1951. After his Navy stint, the Hursts, now with daughter, Susan, lived in Waukegan. Bob had gotten a job with Johnson Motors while Lorraine was a teacher in the town. While still in Illinois, Bobby was an usher at the wedding of Lorraine’s sister, Mary Ellen, on August 2, 1958, in Sheffield, Illinois, to William Hynd; the Hynds were my in-laws. The Hursts lived a short time in Kenosha, Wisconsin, before moving to Florida in 1959. Perhaps the Hursts had heard that yours truly had been born in May that year in Bloomington, Illinois, and wanted to get out of the Midwest!

In Florida, Lorraine provided the financial stability the family needed in her teaching job as the transition took place and Bobby could formulate a business plan. That was typical Lorraine. A more giving person you will never meet, a trait she lavished on her husband, daughter, grandchildren, great grandkids, other relatives, even people who didn’t know she’d helped them out because she did it anonymously. Life was never about herself or possessions, but about making a difference in people’s lives. She taught school in the Orlando area for 30 years, then retired as one of the most deeply loved teachers, adored for her intelligence about what life is all about, caring nature, abhorrence of selfishness and lies, sense of humor, and a crazy infectious laugh and smile. When she died on June 27, 2015, the family asked that in her memory everyone encourage, hug and laugh with a child.

Bobby operated his Bob’s Boats and Motors business from 1959 to 1998 and at some point his advertising jingle became the catchy and wildly popular, “How ’boutcha, Bob?” Bob’s success allowed him the heft to help create a group for the area’s marine dealers called the Central Florida Marine Trades Association. He also had a hand in forming the annual Marine Trades Boat Show. Notable success came selling the Bayliner brand after 1984. Bobby employed family at the shop, including Susan from 1984 to 1998 and, yes, Lorraine, who after her retirement continued being a team player in the family success and worked until Bobby sold his business in ’98. Bob’s “empire” included owning several properties in the area.

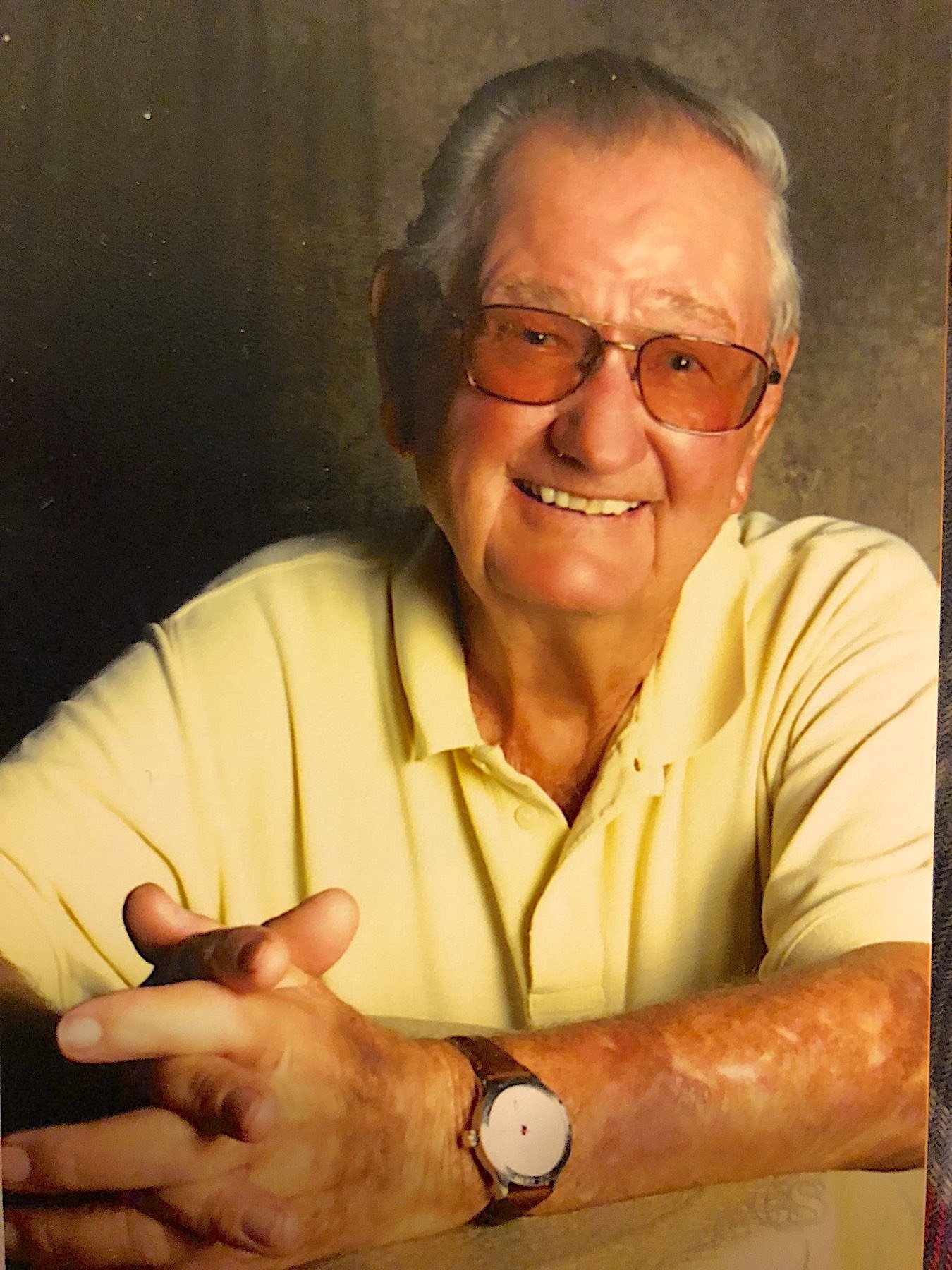

It was in his incarnation as marine wares entrepreneur that I first met Bobby, who died on August 19 at age 94. My wife, Mary, and I went to his and Lorraine’s beautiful home on Merritt Island in 1986, which had a canal in the back that led to the Banana River between the island and Cocoa Beach, a waterway where dolphins and manatees frolicked. We arrived by car on a weekend afternoon. Bobby had been sleeping on the sofa in just a pair of gym shorts. Hardly the attire for a boat-store kingpin or for someone welcoming guests, but it was part of his persona and at home he was casual and relaxed.

Like most of us, Bobby was a man of contradictions, mainly political in my view, but Bobby was strong at departmentalizing life. In contrast to his at-home leisure-wear, at work he wore casual slacks and short-sleeved button shirts, hair neatly combed, a professional look for all work occasions. A smoker, he was finally convinced he needed to quit and one time on a road trip took the pack from his pocket and threw it out the window, and that was it. Everyone who knew—and quickly loved—Lorraine wish she had followed suit.

Bobby knew how to wind down, too. I didn’t know too many other people who knew how to organize fun time as well as he could. When he wanted leisure time, he made sure the time was planned out and arrangements made so when he was ready to enjoy he enjoyed and it provided the desired effect. He told me once that when he took his frequent trips to the Florida Keys (he loved deep-sea fishing), pulling a boat on a trailer all the way from Orlando, he’d hear every clank and rattle and loose wrench from the rear but on the way back his relaxation was so complete that he didn’t hear a thing.

Let’s go back to the name game one more time. How about Bobby Earl Hurst, golfer? What a great name for a pro from the South (the late Chandler Harper, a Virginian, still carried my most favorite moniker for a tour pro). After Lorraine as Bobby’s greatest love, and family, golf was it for him. That was good for our relationship because I was a Golf Digest editor and the two of us connected well about the game. He loved to watch golf tournaments on TV and never missed a single one. We played one or two rounds or hit the range every time we visited from Connecticut. The Schrocks loved Disney, so we made frequent trips spanning 30 years, 1986 to 2015.

It’s not certain when Bobby began playing golf in earnest. But he was known for hitting a bucket of balls every so often as a young man and he would bring Susan with him to hit as well. But because he was working seven days a week for many years to get his business up and thriving, he didn’t pick up the pace as a player until he was in his mid-50s, when he could afford more time away from work. When he sold his business in 1998, the golf floodgates burst open and he was playing a couple times a week, usually with a regular group of pals at places like Winter Pines (Winter Park Pines) in Winter Park and Wedgefield Golf Club in eastern Orlando. Bobby and Lorraine left Orlando in retirement to live in Merritt Island, but when they decided to go back to the city, to Longwood, Bobby still went way out of his way to Brevard County along the Atlantic coast to play with his peeps.

I would describe Bobby as the dream for every golf course, teacher, manufacturer, and, well, damn, as he’d use his favorite exclamation, any business having to do with the golf world! Susan felt he poured himself into being good at golf at the same measure he poured himself into being a good businessman. He took lessons from local pros, supported multiple courses, read every golf publication he could get his hands on, and was addicted to every golf infomercial on the air. Every time I saw him he couldn’t wait to show off a new driver he’d bought on the promise it was the answer to lower scores. I knew better but kept the thought to myself that for thinking of himself as a savvy businessman he sure was the ultimate gullible buyer in going for all the fads. But what I thought was nothing compared to what Lorraine had to endure, seeing her husband buy $500 drivers like they were candy bars; half-eaten ones at that because he’d use them for a while and see how fruitless it was to continue with the club. Lorraine once said they were going to go broke in retirement if Bobby didn’t stop buying. Bobby liked to bet with his golfing cronies but I would “bet” he saved Lorraine from knowing how much money he lost on his bad days, but the common belief is that he won more often than he lost. As an astute businessman he surely would have been more frugal betting if he was always on the losing end. It wasn’t too often that Bobby didn’t make the right bargain for himself and family.

Lorraine knew how to handle Bob’s guff about his golf feats when he would discuss his day’s results. She was an incredible note writer and belongs in the note-writing hall of fame, if there is one, and in one of her marvelous notes to us, dated November 24, 2008, she wrote, “Bob shot an 82 Friday, so he thinks he’s really fine.”

Bobby and I usually played as a twosome and I think we provided for the other person what you’d like in an intimate golf game: playing chit-chat, world affairs chatter, and personal heart-to-heart. We had so many conversations that the golf often was unimportant to the experience. As someone a year shy of my father’s age, Bobby meant a lot to me in a confidante/life advisor sort of way. When he talked his extreme conservative politics, I just said “uh-huh” through it all to indicate I “understood.” I firmly believe that we are such a diverse people that we can’t all have what we want and we need to compromise, as my founding father idol Benjamin Franklin taught. To do otherwise, well, we’re seeing what to do otherwise causes. It would have been futile to try to convince Bobby to admit he saw my point-of-view, and him convince me to see his, but I could have accepted we had differences as long as we agreed to progress on what we could accept between us.

Bobby and I often spoke about what it meant to be a good spouse and how easy it would be to mess up. Driving by an adult club one time en route to golf, he said, never go there: “Why would you want to when you got the real thing at home.” Getting serious another time in one of our latter outings, we talked about being alone if we lost our spouse. He said, if Lorraine died before him, he wouldn’t be long for this world. He said it somberly, almost in a scary sort of way, that made me worried if he would act upon that if it happened. But it made an impact on me of how deeply he felt for Lorraine and we all should be for our spouses, and he made good on that devotion when he tended on Lorraine through her illness and passing.

I want to bring LBJ back into this story because Bobby did speak almost exactly like his fellow Texan. Go to the YouTube video of Johnson announcing in March 1968 that he would not run again for president, and that’s an example of how Bobby spoke and his hesitant pauses. They were distinct and we all enjoyed mimicking him, especially when he was being goofy. “Good Cliff, hit,” would be his out-of-order verbiage when I’d drive. “Damn, Mary,” when my wife would hit a good one off the tee.

He was most endearing when he was goofy. Out at breakfast one morning, he instructed our then school-aged daughter, Joelle, to always go through the little tray of jellies on the table and make sure there were a couple of every flavor. It was important! After we had our last round with him on November 9, 2015—Mary, myself, Bobby, and Rob Clem, his grandson (and our ring-bearer in 1983!)—we are in the photo on the home page—went to the local Burger King, where Bobby and Mary donned paper crowns.

Bobby was average in height and build but his arms and hands were like sledgehammers, thick and meaty. As he passed through his 80s, though, his enthusiasm wound down as his body and game deteriorated. His goal of shooting his age faded as well. When his goal seemed unlikely, his energy level lagged. His final three years as a golfer were spent with Rob taking trips to Topgolf Orlando, at Rob’s suggestion. To do anything else would have been painful due to neuropathy in his feet.

What’s in a name? Bobby Earl Hurst, born on the Fourth of July, was a patriot who served in the American Navy. Bobby Earl Hurst, boat-store owner, was also known as Captain Bob at the store and by his friends and all his employees. Bobby Earl Hurst, who loved his family—and golf—lived his life exactly as he wanted to and lived it to the full.

How ’boutcha, Bob!